Mark Cuban found himself in the middle of a fiery debate on CNBC’s Squawk Box when the topic turned to Vice President Kamala Harris’ proposed tax on unrealized investment gains.

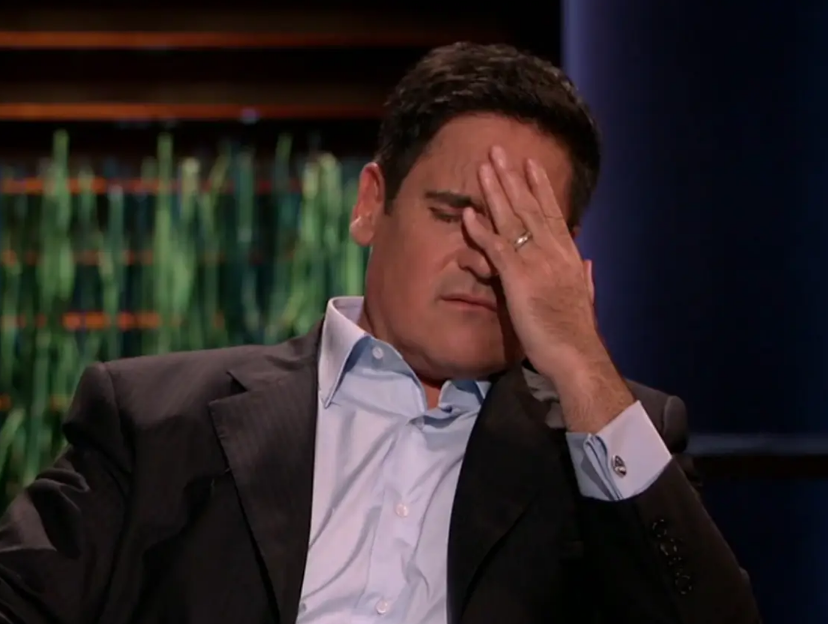

Cuban, never one to shy away from speaking his mind, wasn’t having it, and the discussion quickly escalated into a tense exchange with host Rebecca Quick. The moment became especially memorable when Cuban, visibly flustered, repeated the word “no” a remarkable sixteen times in a row in response to Quick’s pressing questions.

The clash began when Quick suggested that Harris was playing to her voter base, offering policies that sounded good on paper but lacked practicality. Cuban, while acknowledging that he had been in private conversations with Harris’ team, made it clear that taxing unrealized gains would be disastrous for the economy, particularly the stock market.

“If you tax unrealized gains, you’re going to kill the stock market,” Cuban stated, explaining that the policy would force investors to pay taxes on paper profits before they’ve actually sold their assets.

Drawing from his own experience, Cuban referenced the dot-com era when his wealth was tied up in stock, leaving him with little actual cash on hand. Under Harris’ plan, he would have been obligated to borrow money to cover taxes on gains that only existed on paper, a move that could have stifled his ability to grow his business. He stressed that this tax would make private equity firms busier than ever, as investors would need new strategies to mitigate the potential hit from such a policy.

Criticism of the proposal goes beyond Cuban’s objections. Many economists and business leaders have raised red flags over the practicalities of implementing a tax on unrealized gains. The complexities of calculating these gains and the potential for unintended market consequences, such as mass sell-offs, make it a risky proposition.

Moreover, Harris’ plan, though aligned with Joe Biden’s broader efforts to impose a 25% minimum tax on ultra-wealthy Americans, hasn’t gained the necessary traction in Congress, and its chances of becoming law remain uncertain.

As Quick pressed Cuban on whether Harris was out of sync with what voters need to hear, he maintained that Harris’ team had acknowledged the problems with the policy but argued that the details could still be ironed out. Quick wasn’t convinced, emphasizing that the election is just around the corner, and voters need clear policy stances before heading to the polls.

Cuban’s repeated “no, no, no” response was his attempt to stress that working out the specifics was more important than rushing to present a flawless plan before the election.